Print Samples

The Goal

| To get this... | ...to them. | |

|

|

|

Ideas! Imagination! That's where all music starts. A composer will get an idea then write it on music paper or record it. Then that idea grows and takes on different shapes and sizes. Ultimately the final creation must be translated into a form that other musicians can use to help realize that creation, and that's where we come in — the crucial middleman in this entire process. Writers come to us with music in various stages of completion. In the extreme we can get a finished symphonic score, beautifully engraved, from which we must create individual parts for each member of the orchestra; or a barely legible pencil sketch filled with scratched out notes and musical shorthand. Or somewhere in between. |

Whether we are called upon to arrange, to orchestrate, or to prepare the parts, our job is to translate all of this into proper notation in a style that is best suited to the function of the music. For example, a flute part for a symphony musician will have a different look and feel than a flute part for a Broadway show. And a piano part for a published folio will look different than a piano part for a film score. Robert Nowak's work has appeared in the catalogs of many music publishers. And as you can see elsewhere on this site, he has provided written music for many artists and projects. He also has provided specific examples of written music for the New York Times, Random House, and others. Here, then, are some examples — and explanations — of his work. |

How does a piece of music get from the mind of the composer, arranger or orchestrator to the musician's stands? And what do we do to make that happen? Let's take a look at some real music — with helpful "before" and "after" examples.

The Arranger and the Singer...

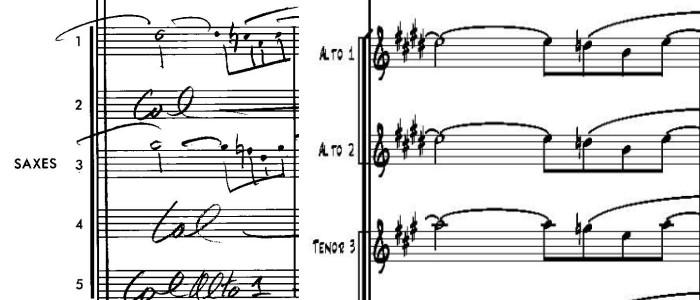

The example below shows measure 49 of Swingin' Away the Blues. The left portion is what Tommy sent Bob — complete with the very common arranger's notational shorthand. The right portion shows what Bob sent back to Tommy. But...you might notice something doesn't look quite right. During rehearsals Ann felt this arrangement would be better for her a step higher. Tommy didn't re-write a transposed version. He left that to Bob. Bob also needed to make sure that Ann's new key was in within the range of each instrument. So, Bob's job was to translate Tommy's pencil score, find and correct any mistakes which even an arranger as good as Tommy Newsom can make in the heat of a deadline and, finally, transpose it into Ann's new key.

Want to see more of Tommy Newsom's chart? Click for PDF of the full "before" page. Click to see the same page "after" Bob did his work.

The Drummer Goes Legit...

Now let's look at a totally different genre. Urban Overture was written by Sherrie Maricle for a "classical" percussion ensemble. You may know Sherrie as a fabulous jazz and big band drummer and leader of the Diva Jazz Orchestra. But Sherrie has her serious side. (Some people know her as Sherrie Maricle, Ph.D.) She is very well known in the serious percussion community as both an educator and published composer. The example below shows a portion of measures 39 and 40 of Sherrie's original pencil score. Next to it is Bob's work on the same portion of the score.

You'll notice that Sherrie's score doesn't look the same as Tommy's. Earlier we said that part of the job of preparing music correctly is to use the proper notational style appropriate to the music. The classical world is accustomed to seeing music printed in a different style than a big band or Broadway pit orchestra uses. It's also part of the copyists job to know the notational style and rules for each type of ensemble and each instrument the composer uses — whether piano, harp, horn or tin can.

Click to see the full page "before" page of Urban Overture. Here's the "after" page.

Congratulations! You've just completed Music Preparation 101. A good copyist must know the language of music. A great copyist knows music inside and out. Bob Nowak is a great copyist.